Build Strong Bones Today: Bone Care Tips for All Ages

Medically Reviewed By:

Dr. Hema Sathish M.B.B.S., D.D(UK)

Dermatologist, Founder of Cureka

Bones are more than just the body’s framework; they are dynamic tissues with roles in movement, protection, blood cell formation, and mineral regulation. Despite their strength, bones are not immune to wear and tear over time. From early development to older age, bones undergo continuous changes in composition, density, and function.

Maintaining bone health isn’t a concern only for the elderly. In fact, the groundwork for strong bones later in life is laid during childhood and adolescence. But regardless of age, there are simple and effective ways to keep bones healthy and resilient.

In this blog, we’ll break down what happens to bones as we age, and share practical bone health tips, including how to eat right, move smart, and support your body’s skeletal system at every stage of life.

Understanding Bone Structure and Function

Bones perform critical mechanical functions: they provide structure, protect vital organs, and enable movement. Equally important are their homeostatic roles, acting as a reservoir for calcium and housing marrow that produces blood cells.

Bone is a composite structure, made of:

- Minerals like hydroxyapatite (calcium and phosphate)

- Proteins, primarily type I collagen

- Cells, including osteoblasts, osteoclasts, and osteocytes

- Water and lipids, which influence flexibility and cushioning

This matrix is designed to be strong yet lightweight. But its properties do not remain constant with age, they evolve in response to biological, nutritional, hormonal, and mechanical factors.

Age-Dependent Changes in Bone Mechanical Behavior

As we grow older, bones undergo significant mechanical changes. During youth, bone formation outpaces resorption, resulting in increased bone mass and strength. However, after peak bone mass is achieved (usually by the early 30s), the rate of bone resorption gradually begins to exceed bone formation.

With aging:

- Bones become less dense and more porous

- Elasticity decreases, making them more brittle

- They are more prone to microdamage and fractures, especially under minimal stress

Mechanical loading such as walking, jumping, or lifting weights stimulates bone remodeling. In older adults, a decline in activity and muscle mass reduces this mechanical stimulus, further weakening bones.

The Bone Cells and How They Age

Bone health is maintained by a balance between three types of cells:

- Osteoblasts (bone builders)

- Osteoclasts (bone resorbers)

- Osteocytes (bone sensors)

With aging:

- Osteoblast function declines, leading to reduced bone formation

- Osteoclast activity may remain stable or increase, accelerating bone loss

- Osteocytes lose sensitivity to mechanical stimuli and nutrient signals

Moreover, mesenchymal stem cells in bone marrow which once produced osteoblasts are increasingly diverted into fat-producing (adipogenic) pathways. This cellular shift reduces the skeleton’s regenerative capacity.

Bone Protein Changes with Age

Proteins, especially collagen, give bones flexibility and help absorb impact. Aging alters these proteins in several ways:

- Collagen cross-linking increases, reducing elasticity

- Accumulated advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) stiffen the collagen matrix

- Non-collagenous proteins that regulate mineralization decline

These protein changes make bones more fragile and susceptible to fractures, even without significant trauma.

Mineral Changes with Age

Bone mineral is primarily hydroxyapatite, but its structure is sensitive to nutritional and physiological shifts. With aging:

- Mineral crystals grow larger and more brittle

- Trace elements like magnesium and carbonate accumulate in abnormal patterns

- Reduced intestinal calcium absorption, especially with low vitamin D, impairs mineral replenishment

With poor nutrition and decreased calcium absorption in the gut (especially with low vitamin D), bone mineral density (BMD) declines. (3) Such changes weaken bones structurally, making them less able to bear load and more prone to fracture.

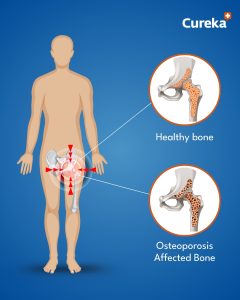

Is Osteoporosis a Disease of Aging?

While osteoporosis is strongly linked to age, it’s not caused by aging alone. It’s a multifactorial condition that results from:

- Hormonal changes, especially postmenopausal estrogen loss

- Poor nutrition, particularly low calcium and vitamin D

- Sedentary lifestyle

- Certain medications or chronic illnesses

Osteoporosis is often called a “silent disease” because bone loss occurs without symptoms—until a fracture happens. That’s why early prevention and regular bone health monitoring are essential.

Nutrition Tips for Stronger Bones

A balanced diet is your first line of defense against age-related bone loss. Nutrients work synergistically, so a well-rounded eating pattern is more effective than any single supplement.

Calcium-Rich Foods

Calcium is the cornerstone of bone structure. Needs vary by age, but most adults should aim for 1,000–1,200 mg/day.

Best sources include:

- Dairy: milk, cheese, yogurt

- Greens: kale, broccoli, bok choy

- Fortified foods: cereals, orange juice, plant-based milk

- Seeds and tofu

Low-calcium diets are often low in other critical nutrients too, such as vitamin D and magnesium.

Vitamin D for Bones

Vitamin D enables calcium absorption and helps regulate bone turnover. It’s produced in the skin via sunlight and found in:

- Salmon, mackerel, sardines

- Egg yolks

- Fortified foods

As people age, their skin becomes less efficient at synthesizing vitamin D, so supplementation may be necessary—especially for those who are indoors often.

Other Essential Nutrients

- Magnesium: Aids bone mineralization (nuts, seeds, legumes)

- Vitamin K: Supports protein synthesis for bone formation (leafy greens)

- Vitamin B6: Important for collagen cross-linking (chickpeas, bananas, poultry)

- Protein: Provides the scaffolding for bone mineral (meat, legumes, dairy)

Bone Strengthening Exercise

Bones respond to mechanical stress by becoming denser and stronger. The best exercises for bone health include:

Weight-Bearing Activities

- Walking

- Dancing

- Hiking

- Jogging

Resistance Training

- Lifting weights

- Resistance bands

- Bodyweight exercises

Flexibility and Balance

- Yoga

- Tai Chi

- Pilates

Regular movement also improves muscle strength, which supports the skeleton and reduces fall risk a major cause of fractures in older adults.

Bone Health Tips by Age

- Infants & Children

- Ensure adequate calcium and vitamin D from diet and sunlight

- Encourage physical play to stimulate bone growth

Teens

- Peak bone mass is achieved by age 30—make these years count!

- Focus on high-calcium foods and exercise

Adults

- Maintain healthy lifestyle habits to preserve bone mass

- Monitor for conditions or medications that may affect bones

Older Adults

- Increase calcium and vitamin D intake

- Prioritize weight-bearing exercise and fall prevention

- Get regular bone density scans (DEXA) if at risk

Lifestyle Habits That Support Bone Health

Building and maintaining bone strength goes beyond diet and exercise. Consider these habits:

- Avoid smoking, which reduces blood supply to bones

- Limit alcohol, which interferes with calcium absorption

- Manage chronic conditions like diabetes and thyroid disorders

- Stay mobile, even light movement helps prevent bone loss

For postmenopausal women or older adults with significant risk, healthcare providers may recommend bone-preserving medications like bisphosphonates or hormone therapy.

Conclusion:

Strong bones are not built in a day, but every day counts. Whether you’re 16 or 60, investing in bone health today means protecting yourself from disability, fractures, and frailty in the future. With a balanced diet rich in calcium and vitamin D, regular bone strengthening exercise, and lifestyle awareness, you can actively shape your skeletal health.

Remember: bones may age, but with the right care, they don’t have to grow weak.

FAQ’s

1.How can I improve my bone health at any age?

Improving bone health can be achieved by maintaining a balanced diet rich in calcium, vitamin D, and magnesium, engaging in regular weight-bearing exercise, and avoiding smoking and excessive alcohol. These steps help support bone density and strength at any age.

2.What are the best exercises for strong bones?

Weight-bearing exercises like walking, running, dancing, and strength training are excellent for building bone strength. Activities that involve lifting weights or using resistance bands are particularly beneficial for maintaining healthy bones.

3.Can diet prevent bone loss?

Yes, a healthy diet plays a crucial role in bone health. Consuming foods rich in calcium (such as dairy products), vitamin D (like fatty fish and eggs), and magnesium (found in leafy greens and nuts) can help prevent bone loss and improve bone density.

4.How does age affect bone health?

As you age, bone density naturally decreases, particularly in women after menopause due to reduced estrogen levels. It’s important to prioritize bone care with diet, exercise, and lifestyle changes to prevent bone density loss as you age.

5.When should I start focusing on bone health?

It’s never too early to start focusing on bone health. Bone-building habits should be developed in childhood and continue into adulthood. However, taking extra steps in your 30s and beyond can prevent or slow down bone loss as you age.

References:

- Aging and Bone – 2010 Dec – https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2991386/

- Age considerations in nutrient needs for bone health – 1996 Dec – https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8951731/

- Aging and Bone Metabolism – 2023 Jan – https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36715278/